Researchers Determine Structure of a Molecular Complex Critical for Joining Cells Together

Scientists from the Florida campus of The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have for the first time determined the structure of a large molecular complex that plays a vital role in cell adhesion, the force that binds cells together in all animals, including humans—without it, there would be a tendency for them to simply fall apart.

The new study, led by Scripps Florida Associate Professor T. Izard, was published December 8, 2014, and highlighted in an “In this Issue” article by the Journal of Cell Biology.

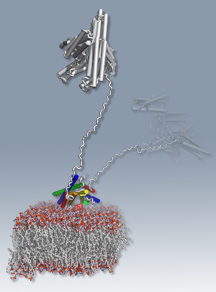

This critical cell binding is done through specialized cell surface adhesion complexes called adherens junctions (which direct the formation of tight, Velcro-like contacts among cells), other structural proteins called F-actin (the “F” stands for filament) and focal adhesion complexes. This process is necessary for cell migration and morphogenesis, the shaping of tissues and organs that is an important part of development.

In the study, the scientists produced an x-ray crystallography image of the cytoskeleton protein vinculin, an essential regulator of adherens junctions and focal adhesion, binding with a fat or lipid known as PIP2, a major component of all cell membranes. The images revealed that PIP2 binding alters vinculin structure to direct oligomerization—the linking together of a few protein or nucleic acid macromolecules—which, in turn, stabilizes focal adhesion complexes.

The structural findings also revealed that vinculin’s PIP2 and actin-binding sites are distinct, suggesting that the protein may be able to bind to both molecules simultaneously.

In additional experiments, the scientists determined that PIP2 binding is necessary for maintaining optimal vinculin dynamics, turnover in F-actin and for cell migration and spreading.

The structure and functions of other lipid-and-actin-binding cytoskeleton proteins may have similar mechanisms of action for PIP2, according to the authors.

In addition to Izard, authors of the study, “Lipid Binding Promotes Oligomerization and Focal Adhesion Activity of Vinculin,” were Krishna Chinthalapudi, Erumbi S. Rangarajan and Dipak N. Patil of TSRI; and Eric M. George and David T. Brown of the University of Mississippi. For more information, see http://jcb.rupress.org/content/207/5/643

The work is supported by grants from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, the National Institutes of Health; the US Department of Defense; and by the State of Florida.

Send comments to: press[at]scripps.edu