TSRI Research Suggests Powerful Tool for Detection and Treatment

of Anthrax

By Jason Socrates

Bardi

Human antibodies against Bacillus spores, of which

one species is the cause of anthrax, have been identified

by researchers at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI). These

antibodies could be used to detect the presence of anthrax

and other harmful spores in powders and to protect those exposed

against lethal infections.

In the current issue of the journal Proceedings of the

National Academy of Sciences, scientists Bin Zhou, Peter

Wirsching, and Kim D. Janda of the Department of Chemistry

and The Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology describe the

antibodies.

"The antibodies," says Janda, who holds the Ely R. Callaway,

Jr. Chair in Chemistry, "give you the ability to dissect very

quickly what you have—whether it's a hazardous spore

preparation or just plain baby powder."

Using donated blood, the researchers were able to find a

number of human antibodies that were all highly specific for

spores of Bacillus subtilis, a close cousin of Bacillus

anthracis which is the causative agent of anthrax, and

11 other types of bacterial spores. Work on Bacillus anthracis

itself is currently getting underway.

The researchers found the antibodies using phage display,

a method for selecting from billions of antibody variants

only those that bind to a particular target. In the technique,

the antibody repertoire obtained from white blood cells is

fused to a viral coat protein of the phage—a filamentous

virus that infects bacteria—to create an antibody "library."

Since the phage virus displays the antibodies on the surface

of the virion, it makes them easy to select for in vitro

Bacillus spores. Those that cannot bind are washed away,

while those that bind to the spores are selected.

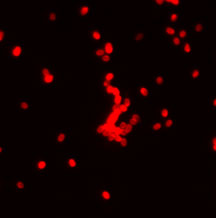

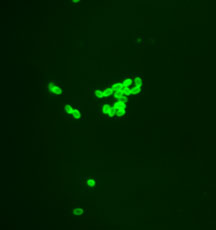

By attaching a fluorescent chemical to the antibodies, Janda

and his colleagues could look under a specially equipped microscope

and quickly determine whether a powdered sample had any spores

present. They could even detect a single spore.

"We've shown for the first time that human antibodies can

recognize spore surfaces," says Janda, who adds that the antibodies

might make a powerful and convenient tool for detecting anthrax.

Moreover, antibodies that bind to spores have important

implications for treating individuals who are exposed to anthrax.

Since the antibodies come from humans, they could be given

to individuals to passively immunize them—the antibodies

would help to clear anthrax spores from the individual's system.

And, because of the ease of producing and administering antibodies,

they represent a simple, inexpensive, and potentially powerful

therapy.

The research article "Human antibodies against spores of

the genus Bacillus: a model study for detection of

and protection against anthrax and the bioterrorist threat"

is authored by Bin Zhou, Peter Wirsching, and Kim D. Janda

and appears in the April 16, 2002 issue of Proceedings

of the National Academy of Sciences.

The research was funded in part by The Skaggs Institute

for Chemical Biology.

Link:

San

Diego Union-Tribune coverage

|

By attaching a fluorescent chemical

to the antibodies, investigator Kim Janda and his colleagues

could look under a specially equipped microscope and quickly

determine whether a powdered sample had any spores present.

Here, the Bacillus subtilis spores are shown bound to FITC-labeled

phage (top) and rhodamine-labeled phage (bottom).

|