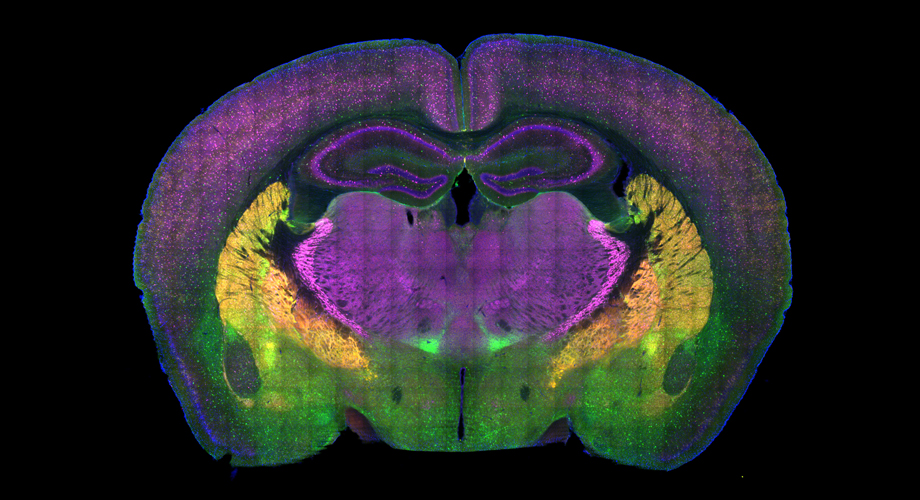

A cross-section of a mouse brain reveals some of the regions involved in the choice between social approach and avoidance. Credit: Page lab, Scripps Research, Florida. (Red is a genetic reporter for GABAergic neurons, green and magenta are immunohistochemical markers for subsets of GABAergic neurons, and blue is DAPI, a nucleic acid stain.)

Autism researchers map brain circuitry of social preference

Discovery empowers research into needed therapies, scientists say.

July 14, 2020

JUPITER, FL — Some individuals love meeting new people, while others abhor the idea. For individuals with conditions such as autism, unfamiliar social interactions can produce negative emotions such as fear and anxiety. A new study from Scripps Research reveals how two key neural circuits dictate the choice between social approach and avoidance.

Neuroscientists who study autism have sought to define the brain circuits underlying these challenges, to enable more precise diagnosis, and to develop protocols for testing the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions. Brain mapping efforts have implicated multiple areas, including the emotional center of the brain and the region responsible for coordinating thoughts and actions. Assigning cause and effect to changes in these regions to the symptoms of autism, however, has been challenging.

The study from the lab of neuroscientist Damon Page, PhD, uses a variety of innovative techniques to address this challenge, finding two specific circuits capable of independently controlling social preference in mice. Both link the areas of higher-level thought and decision-making in the prefrontal cortex to the emotional regulation center of the brain, the amygdala.

Sociable animals like mice – and humans – generally seek out social engagement, which produces benefits including increased resilience to stress, Page explains. But in conditions such as autism, schizophrenia and others that feature social impairments, an unexpected social encounter may produce a negative emotional reaction. Difficulty communicating and interacting with others is a hallmark of autism spectrum disorders, which now affect 1 in 34 U.S. boys and 1 in 54 girls age 8, according to the National Institutes of Mental Health.

“To understand something properly, you need to know where to look. It’s a needle-in-the-haystack problem,” Page says. “Understanding how this circuit works normally enables us to now ask the questions, ‘How is this wiring changed in a condition like autism? How do therapeutic interventions impact the function of this circuit?’”

The group found that one neural circuit connecting the mouse infralimbic cortex to the basolateral amygdala impairs social behavior if its activity is dialed down. The other key circuit connects the prelimbic cortex to the basolateral amygdala. Dialing up activity of that circuit produced similarly impaired social behavior, says Aya Zucca, the study’s co-first author.

Zucca notes that both mice and humans use corresponding brain regions to process social information, so the mouse model is a good one for studying these issues.

“Using a technique called optogenetics in mice, we controlled the neurons that were active during negative experiences at the precise time of social engagement. This manipulation of the circuit resulted in them avoiding social interaction. It’s a bit like when you see a friendly face, but then have a flashback of a negative experience that’s strong enough to make you decide to walk the other way.”

With this social preference circuitry now identified, other questions can be addressed, such as, how this circuitry is wired during development, and whether genetic or environmental risk factors for autism cause mis-wiring of this circuitry, Page says.

“The brain circuitry underlying the social symptoms of autism is almost certainly highly complex and we’re just beginning to map it,” Page says. “But this study adds an important landmark to that map.”

The study, “Social Behavior Is Modulated by Valence-Encoding mPFC-Amygdala Sub-circuitry,” appears in the journal Cell Reports on July 14. In addition to Page and Zucca, contributors include co-first author Wen-Chin Huang, currently at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Picower Institute for Learning and Memory, and Jenna Levy, of Scripps Research.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant R01MH105610, Ms. Nancy Lurie Marks, the Fraternal Order of Eagles, the American Honda and Children’s Healthcare Charity, and an anonymous donor.

For more information, contact press@scripps.edu