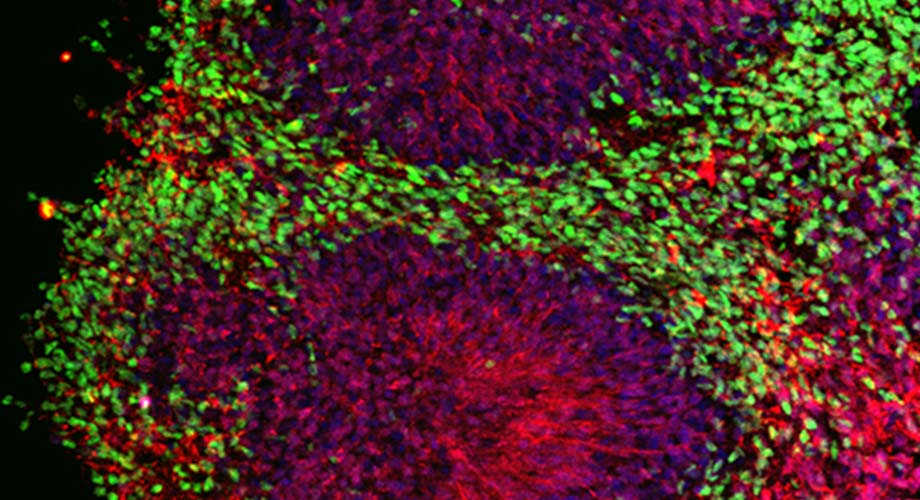

The drug was tested on a "mini-brain," also known as a cerebral organoid (pictured), composed of induced pluripotent stem cells from an Alzheimer's patient. Colors highlight the various cell types. (Image courtesy of the Stuart A. Lipton laboratory, Scripps Research)

In human mini-brain experiments, drug rebuilds nerve connections lost to Alzheimer’s

The drug is also being evaluated for COVID-19, as it is known to reduce viral activity and possibly protect the brain from virus-related damage.

May 29, 2020

LA JOLLA, CA—An experimental drug for Alzheimer’s developed at Scripps Research reached a key milestone this week, with publication of a study showing that when tested in human "mini-brains," it protected brain connections that are typically destroyed in patients with the neurodegenerative disease.

And in an interesting twist, the drug is separately being explored for its potential to help fight key symptoms of COVID-19—a project for which the drug’s inventor, Scripps Research Professor Stuart Lipton, MD, PhD, just received funding from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine and the National Institutes of Health.

The drug, patented under the name NitroSynapsin, is a novel combination of two FDA-approved medicines that together may halt excessive, seizure-like electrical activity that occurs in the brain of those who have Alzheimer’s. This activity contributes to the loss of brain synapses, which are the connections between nerves cells that are critical for memory and other brain functions.

A mini-brain success story

In a study that appears May 29 in Molecular Psychiatry, Lipton and his team were able to show that NitroSynapsin not only prevents the loss of human brain synapses but promotes the regrowth of lost synapses. They tested the drug both on mice and on 3-D mini-brains, also known as cerebral organoids, that are created using skin cells from Alzheimer’s patients.

“We were able to show, for the first time, that the drug works in a human context,” says Lipton, who is also the director of Translational Neuroscience and the Hannah and Eugene Step Chair at Scripps Research, and a practicing clinical neurologist. “This is a significant finding, as experimental drugs for Alzheimer’s and other progressive brain diseases have an unfortunate track record of working well in mice, then failing when tested in people.”

Notably, the drug does not attempt to treat Alzheimer’s by targeting amyloid beta plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles, the misfolded proteins expressed in Alzheimer’s brains. Researchers have tried for decades to address the misfolded proteins, with little success.

“Everyone is now looking for a way to treat the disease at an earlier stage,” Lipton says. “Interestingly, our findings suggest that it may be possible not only to intercede earlier, but also later, when synapses are already damaged.”

That means Alzheimer’s patients may be able to restore synaptic connections after extensive plaques and tangles have formed in their brains, notes postdoctoral fellow Swagata Ghatak, PhD, first author on the study.

The study showed that the small clumps of amyloid beta protein that were thought to injure synapses directly actually induce the release of excessive amounts of the neurotransmitter glutamate. In this case, glutamate is released from brain cells called astrocytes, which are adjacent to nerve cells. Normal levels of glutamate promote memory and learning, but excessive levels are harmful to synapses. In patients with Alzheimer’s, excessive glutamate contributes to the dangerous level of electrical activity in the brain, resulting in synapse loss.

The COVID-19 connection

COVID-19 emerged as a global pandemic just as Lipton and his team were putting the finishing touches on their promising Alzheimer’s study. Lipton read with concern about neurological symptoms that arise in many severe cases—symptoms that are also thought to be due, at least in part, to excessive release of glutamate in response to viral inflammation.

Lipton knew that a drug called memantine (marketed in the U.S. as Namenda), which is related to NitroSynapsin but less effective in pre-clinical models, had its origins as an antiviral medication. In fact, Lipton had developed, patented and gained FDA-approval for memantine to be used to treat moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s about 10 years ago, some 40 years after similar drugs had been used as antivirals.

Because COVID-19 is caused by a virus—a coronavirus known as SARS-CoV-2—Lipton and colleagues reasoned that NitroSynapsin might also work for those patients.

Calibr, the drug discovery and development division of Scripps Research, then began screening NitroSynapsin and related compounds for efficacy against COVID-19, and found that several of these compounds stopped the virus in its tracks, at least in a test tube. The California Institute for Regenerative Medicine recently approved a grant to Lipton to help facilitate this project, which is also supported by the National Institutes of Health and the philanthropic organization Fast Grants.

“Finding a drug that positively affects the course of COVID-19 infections by protecting the nervous system and limiting viral infectivity would have tremendous benefit,” Lipton says. “We are all really excited by this possibility.”

The family of drugs related to NitroSynapsin has been licensed to EuMentis Therapeutics Inc., which is planning a first-in-human clinical trial later in 2020 or early 2021 for Alzheimer’s disease or for autism spectrum disorder (ASD), another malady in part due to excessive electrical activity in the brain.

The study, “NitroSynapsin ameliorates hypersynchronous neural network activity in Alzheimer hiPSC models,” was made possible with funding by the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

In addition to Ghatak and Lipton, other scientists involved in the study are Nima Dolatabadi, Henry Scott, Dorit Trudler, Yin Wu, Rajesh Ambasudhan, Tomohiro Nakamura, and Maria Talantova from Scripps Research, and Richard Gao and Bradley Voytek from the University of California, San Diego.

For more information, contact press@scripps.edu