|

(page 3 of 3)

Sunday

On Sunday morning, I sleep in an extra hour and catch up

with some writing and photography. In the afternoon, I go

to hear Dr. Bloom's remarks at the seminar he organized, "Neuroinformatics:

Genes to Behavior." Much of the session describes various

database projects in neuroinformatics, a field that represents

a confluence of studies in neurological and cognitive functioning

and the science of managing and mining this vast amount of

information.

In neuroinformatics, databases are employed to store large

sets of data, such as on scanned brain sections. "Brain browsers"

and other software allow researchers to access, view, and

analyze the data. Significantly, researchers in other laboratories

can access the data over the internet, and ask new questions.

Also "meta" analyses across multiple data sets can be performed

on data that would otherwise be left to gather electronic

moss.

"Information that would ordinarily reside in a laboratory's

archive [could then] be available to the public," says Bloom.

Later that day, everyone is talking about the weather. Snow

has all but shut down the East Coast. Anyone from the east

who was planning to come to the conference today will not

arrive, and anyone who was planning to leave early will be

stuck or delayed as some two feet of snow falls on every runway

from Washington to Boston.

Monday

With most of the receptions and schmoozing events over,

I decide to concentrate on attending scientific symposia and

learning lots of new things in science.

In fact, I find great joy in doing the conference equivalent

of channel surfing—going in and out of as many presentations

as I can politely manage (luckily, the doors are at the back

of the rooms and always open). I listen to a discussion of

childhood infections in England and Wales and the ecology

of infectious diseases, a description of the molecular correlates

of post-traumatic stress disorder, an analysis of tobacco

use by schizophrenics, a presentation on the structures called

neuronal spines, and a presentation that coupled cholera outbreaks

with the climate.

That evening, I attend a delightful lecture titled, "Bose-Einstein

Condensation: New Results from the Ultracold Frontier" by

Eric Cornell of the National Institute of Standards and Technology

and Carl E. Wieman of the University of Colorado. Cornell

and Wieman are the winners, along with Wolfgang Ketterle of

Germany, of the 2001 Nobel Prize in Physics for achieving

Bose-Einstein condensation—a new form of matter predicted

in the 1920s by Albert Einstein and the Indian physicist S.N.

Bose.

Looking around at the audience, which is highly populated

with what look like high school and college students, I can't

help but to wonder how many of these young minds will themselves

be inspired to study science as a career.

Tuesday

On that high note, I pack my bags—a major hour-long

effort because I forgot to leave room for all the free pens

(and I have a LOT of free pens).

Coincidentally, Dr. Bloom is taking the same plane back

to San Diego. I congratulate him on what has been a terrific

meeting. "How do you feel now that you are done?" I ask him.

"Exhausted," he says, smiling.

1 | 2 |

3

|

"Information that would ordinarily reside

in a laboratory's archive [could] be available to the public,"

says Bloom at the seminar he organized, "Neuroinformatics:

Genes to Behavior."

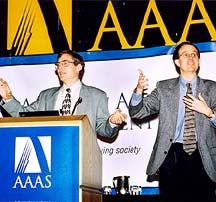

Nobel Laureates Eric Cornell, right,

of the National Institute of Standards and Technology and

Carl E. Wieman of the University of Colorado, left, present

a lively talk titled, "Bose-Einstein Condensation: New Results

from the Ultracold Frontier." "Evaporative cooling is the

hottest thing in cold," says Cornell.

|