Way Down Below the Ocean

By Eric Sauter

David Shin of the Scripps Research Institute's Tainer lab was picked the old fashioned way to go on the Alvin, the deep sea submersible operated by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, to collect deep sea worms for the lab's research. "I volunteered," he said.

According to Shin, anyone who plans to go down in the Alvin needs to take a crash course to learn, among other things, emergency procedures, which can seem a bit superfluous. (If you're roughly two miles underneath the ocean and things went really wrong, precisely what could you do?)

"I think part of what the training is about is checking how often you look up at the hatch," Shin said. "If you look up too much, that means you're claustrophobic and they won't let you descend."

Some caution is probably in order, as the human space in the Alvin is a six-foot-diameter sphere. Anyone working in the submersible, Shin said, basically has to lean against pads attached to the curve of the interior walls. Hardly better off, the pilot sits on a metal box with a pad. Three people, including the pilot, make the descent.

In Shin's case, that was approximately 2,500 meters (roughly a mile and a half) below the surface to the home of Alvinella pompejana, the deep sea worm named after the same Woods Hole submersible and the city of Pompeii buried by an eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in 79 AD. The worm turns out to have some special properties, including an enzyme that could shed light on amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), which make it worth the unusual trip. (See "The Conqueror Worm.")

The first part of the journey included almost a week to get to the site, an isolated part of the Pacific Ocean. "We were directly west of Costa Rica," said Shin. "We'd never see another boat or even lights from a plane. For days, all we could see was the horizon. It was like where the island seems to be on Lost."

Even once at their destination, the trip involved a lot of wait time. About 20 scientists took turns making the descent, two at a time with a pilot.

Shin says that when it's time to go down in the submersible, which has a car stereo built in among the other controls, many Alvin pilots like to play The 1812 Overture as they descend, a bit of added excitement—as if going a mile and a half beneath the surface needed any more excitement.

"I got a little anxious the night before, sitting up, asking myself just what I was doing there," Shin admitted. "But once I got inside, there were things to do. It's a little surreal because there's not a lot of acceleration. It's actually smoother than flying in an airplane."

Going down, the Alvin's speed is about half a mile an hour, so it takes roughly two and a half hours to get to the bottom. The smooth ride changed once they arrived at the hydrothermal vents, when the water flow coming out of the vents and some ocean currents made it difficult for the pilot to steer.

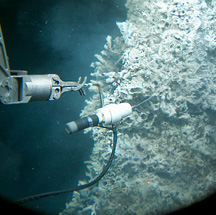

"It got pretty hairy when we got to the site," Shin said. "The pilot had to manipulate the robot arms to get the worm samples and try to keep the submersible from floating into the vent structures, so there were times when I had to remain perfectly still."

Shin was down on the ocean floor for five hours, before it was time to take the two and a half hour trip back up.

The researchers don't keep the worms under pressure as they surface, so the worms don't survive the trip topside. The interesting thing is that they don't die from the change in pressure; they can't survive in the "cold" once removed from the vents.

One experiment that seems to be part and parcel of almost any Alvin expedition is the bag of Styrofoam cups on board to help school children understand the effects of pressure change while diving. "The cups go in a mesh laundry bag attached to the outside of the submersible," Shin said. "They shrink to about a quarter of their original size during the trip."

Despite the dangers, Shin is ready to go back and do it all again if the lab needs more worm samples.

Send comments to: mikaono[at]scripps.edu

Research Associate David Shin traveled about a mile and a half below the surface of the ocean to collect specimens of Alvinella pompejana, a deep sea worm that is helping the Tainer lab shed light on amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

View from an Alvin Submarine porthole 1.5 miles below the ocean surface: A water sampler held by an Alvin robotic arm is being used to sample the environment of an Alvinella pompejana worm tube prior to extraction of a worm from the hydrothermal vent.